I’ve heard it often: Indie music means bad sounding music, in other words, it’s shitty!

First, indie music is often confused with music recorded in a garage by inexperienced musicians with little or no knowledge of recording and mixing, and sometimes less than adequate equipment.

It’s also confused with a genre that would be some kind of lo-fi punk alternative.

This is why, more often than not, I would use the term “unsigned” rather than “indie” to talk about independent music, recorded by talented musicians and producers all around the globe, in every possible genres you can imagine.

Now, while it’s true that some of it can sound bad, it’s detrimental to think that all of it does, and I would argue that more and more, with the prices and quality of recording gear and digital audio workstations (DAW for short) being so affordable nowadays, and tons of resources on how to record and mix, the end result is getting better and better and more and more unsigned artists are producing quality music.

Still, there are some things that contributes to the myth:

1/ the fact that people are listening on devices that are less than adequate to get a good sound (phones, tablets and laptops speakers are not meant to be hi-fi, and even most bluetooth smart speakers are too often synonym of lo-fi, no bass, mono sound)

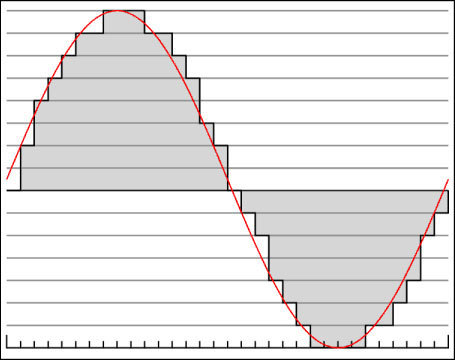

2/ streaming platforms and internet radios are using low rates* mp3 quality to air the music, this is because bandwidth has a cost, in terms of speed, and also in terms of prices when it comes to the power of computers able to sustain hundreds or thousands of listeners in a continuous stream. This power cost also translates directly to services costs that radios are subject to.

* streaming rate is measured in kbps, short for kilo bits per second, this is the amount of data that is used to reproduce the sound - the higher the better, up to 320 kbps which is the upper limit and almost lossless.

Now there is a reason why most streaming platforms (like SoundCloud, Spreaker, or even Spotify in their free tier) and most internet radios are streaming at 128 kbps mp3 or more. They have recognized that this is the absolute minimal limit when it comes to listenable quality. Anything under that rate is creating so much artifacts and distortion to the sound that it’s barely recognizable anymore.

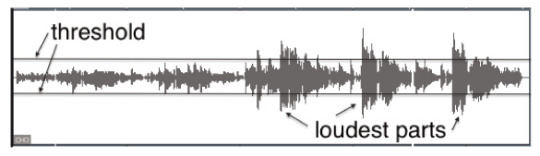

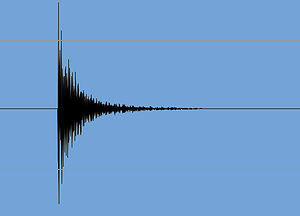

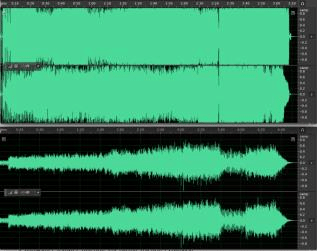

Check out this example of a snippet compressed at 128 kbps and the same snippet compressed at 64 kbps. You will hear the enormous difference between the two, check out how muffled the 64 kbps mp3 sounds, how much the cymbals are drowned in a kind of swirling phase artifact, and how horrible this truly is, it’s even worse that cassettes were back in the 80s…

No matter what device you are using I bet you will be able to hear the difference!

You can go back and forth between two snippets in the player below (opens in a new tab/window):

To me the 64 kbps version is hardly listenable. I wouldn't want my music to sound this bad, I bet most indie artists will agree.

Anyway, when you’ll hear a shitty sound don’t just assume the source music itself has been poorly recorded and mixed, check that the streaming rates you are served are not below the minimum of 128 kbps, I and every unsigned artists striving to produce great sounding records will thank you!